Some select articles I’ve written for the Eastern Mass Hawk Watch annual newsletter over the past few years. As the newsletter editor, I’ve had a great chance to explore many aspects of our organization and the birding world for the membership. Here’s a few feature articles that I composed with the help of some of EMHW’s extended family.

(2023) Conserving American Kestrels in Berkshire County

(2023) A Rookie Season To Remember

(2022) A Rarity for the Ages: The Steller’s Sea-Eagle in New England

(2021) The Kestrel from Across the Pond

(2023) Conserving American Kestrels in Berkshire County

Catching up with Ben Nickley of the Berkshire Bird Observatory

By Brian Rusnica, President, EMHW

One of EMHW’s newest conservation project sponsorships is with the Berkshire Bird Observatory and their parent organization, Green Berkshires. Director Ben Nickley leads the BBO’s conservation efforts, monitoring both breeding and migratory birds throughout the South Taconic Mountains. This year, the BBO’s American Kestrel nest box project is in full swing. With the help of a team of volunteers, the BBO now boasts a sizable collection of 23 nest boxes across prime habitat on a variety of state and town lands, protected organic farms, and select wildlife management areas.

The BBO Kestrel project is in just its second season. Ben started the work in 2022 as a side venture apart from his full-time focus of songbird banding and research at Jug End State Reservation. The idea was sparked by Art Gingert, a conservationist who Ben says has been “an ambassador for Kestrels for decades in Connecticut.” Art has worked with the Sharon Audubon Center to place dozens of Kestrel nest boxes all over the state. Being just over the border in southwestern Massachusetts, Ben connected with Art and received advice and valuable contacts. Ben worked with State Ornithologist Dr. Drew Vitz, MassWildlife, and enlisted help from a team including John Tower, Ben Barrett and Carl Nelson to stock the project with boxes. Nelson has been building Kestrel boxes for MassWildlife for years. By the end of the spring, the first BBO boxes were up and running. That initial breeding season saw early success: 13 Kestrels fledged from three occupied boxes.

One thing that Ben really appreciates about the Kestrel project is the ”tangible conservation results. You are contributing to local and regional populations, with results that you can see and touch.” Those real results drive human connection and have tremendous potential to further outreach and education as the project expands. When the Kestrel chicks reach a certain size, they are banded by Ben with an aluminum USGS band. This enters the birds into the national tracking database where their data can be recorded throughout their lives. Ben notes that volunteers are especially ecstatic to experience the banding process: “Who doesn’t want to see a baby Kestrel in their hands?”

The project aims to help stabilize the declining American Kestrel population, but Ben is also interested in learning what happens to the birds that breed in the area. “It’s a really interesting question to think about – where do the birds that fledge from our boxes end up? Do they stick around in our region? Will they come back and use our other boxes in the future?” Over time, Ben hopes to grow the project with a short-term goal of 30-35 total nest boxes. With enough data, Ben aims to “eventually do our own local analyses and try to understand what’s going on with the birds in our region. We hope to increase box occupancy, and learn about what features in the landscape are productive for Kestrels.”

The BBO project shares a common bond with EMHW, as both organizations contribute their datasets to national efforts. Ben notes, “we share our data as part of the American Kestrel Partnership under the Peregrine Fund. All of our data goes up to them for continental-scale analysis. Contributing to the bigger data set informs conservation and helps us understand declines both regionally and on a larger scale.”

Ultimately, the reason why Ben dedicates so much time and passion to the project is his fondness towards the species. “The birds are the reason behind it…they’re inspiring birds – just amazing pocket falcons.” Ben shared a serendipitous moment during a songbird banding session last spring that brought things full circle for him. While he had banded thousands of songbirds, he was shocked to see that an American Kestrel, a male, had wandered into one of his Taconic Mountain mist nets. It would be the first Kestrel he had ever handled. As he untangled the bird to inspect it, he noticed it was banded. Checking the band number in the database, he was stunned to find this male to be one of Art Gingert’s birds that had traveled in from Connecticut. It was inarguable evidence that Art’s efforts were showing expansive results, and Ben felt the inspiration to carry on that mission and push it even further. The BBO Kestrel nest box project hopes to pass on that same inspiration to everyone who learns about their Kestrels, all while providing real, tangible conservation results for our region.

(2023) A Rookie Season To Remember

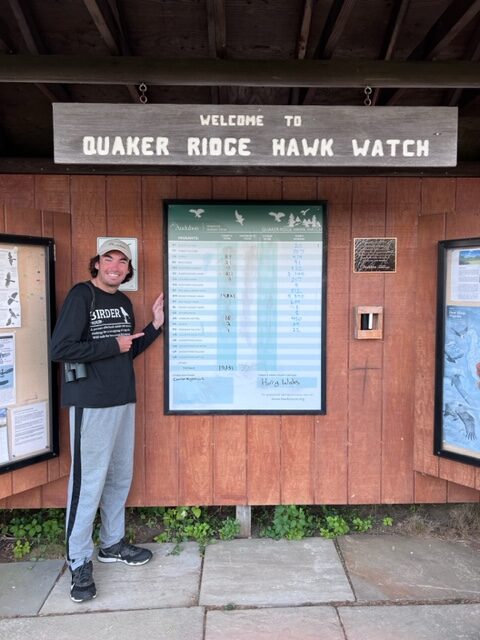

Catching up with Harry Wales, Official Counter at Quaker Ridge Hawk Watch

By Brian Rusnica, President, EMHW

In September, hawkwatchers eagerly refresh the Hawkcount.org website, waiting for counts to roll in from the regional sites. On September 16th of last year, the Quaker Ridge hawkwatch report surely shocked many watchers. The Greenwich, CT site had an astounding 15,131 migrant raptors – a single-day number not seen in close to a decade in New England. Making that news even more exciting was knowing that Harry Wales was the official counter that day – a name and face well known to the EMHW family.

Harry began birding at a young age, starting up the hobby with his dad, Herrick. Harry recalls that a Rough-legged Hawk was his “spark bird” that really got him going: “One thing led to another, and I got obsessed with birds: I loved getting out, observing the behavioral clues with different species, learning migration and flight patterns.” Harry remembers his formative first hawkwatch too – a “good Plum Island day” of 200-300 migrants when he was in 8th grade.

Over his young adult years, Harry became a regular fixture at the Plum Island watch, and also traveled to Wachusett Mountain in the fall. Hawkwatching became more of a passion, something even worth missing school for, if the winds were right. At the EMHW sites, Harry learned from counters like Paul Roberts, Bob Secatore, and a host of other observers and was often commended for his “young eyes” and ability to quickly pick up birds at great distance.

It wasn’t long before Harry became an extremely formidable general birder. Yet birding and the natural world ended up being more than just a hobby – Harry attended the University of New England as an Environmental Studies major, graduated in 2022, and landed his first counting position at Quaker Ridge through the Greenwich Audubon Center last fall.

As the season began, Harry felt “extremely honored, excited, and nervous.” He recalls the first migrant counted in August was an Osprey, and things were quickly off and running. Just a few weeks into the campaign, the massive September 16th flight broke loose. The day was “pure chaos” according to Harry. During an early walkaround, he noticed Broad-wing kettles forming immediately: “The birds were already moving and I thought this could be really big.” The morning count was a stunning 3,000 birds – and many, many more were on the way. Observers found kettle after kettle, including a single group Harry estimated at an enormous 1,100 birds. While he gauges that many hawks may have been missed in the chaotic flight, the final count ended with over 15,000 raptors – an unforgettable day.

As the weather got colder, Harry still turned up huge days and special birds. On October 28th, he counted 532 Red-shouldered Hawks – a single-day site record and one of the highest migrant flights ever recorded of this species in the east. That same day broke the site record for Cooper’s Hawk (115) and Turkey Vulture (391) as well. He even managed to squeeze in two Swainson’s Hawks along the way. All told, records were set for four species at Quaker Ridge (Red-shouldered Hawk, Cooper’s Hawk, Bald Eagle and Turkey Vulture). The final count of 35,405 birds was the largest in almost 30 years.

As for what’s next for Harry – he hopes to enter a Master’s program where can further examine the relationship between climate change and bird populations. But first – another season at Quaker Ridge in fall 2023. While last year will be hard to repeat, Harry is still excited: “I love counting hawks – I’m a numbers guy. I really enjoy looking at totals and racking up the season numbers.”

While Harry grew up at Eastern Mass Hawk Watch sites – his future in birding and conservation will surely take him around the globe. Bucket list hawkwatch sites he wants to visit include “Corpus Christi in Texas, Cape May in New Jersey, Hawk Ridge in Minnesota, and Vera Cruz in Mexico.” Even though it may take a while, he’s OK with that: “I’ll be an old man and I’ll still be counting somewhere.”

(2022) A Rarity for the Ages: The Steller’s Sea-Eagle in New England

By Brian Rusnica, President, EMHW, with Will Martens, Paul Roberts and Bob Secatore

It’s not every day that a birding story becomes international news, but for a few weeks this Winter, that exact scenario unfolded in our regional backyard. The appearance of Massachusetts’ first-ever Steller’s Sea-Eagle (Haliaeetus pelagicus) in December 2021 made major waves and grew into one of the biggest birding stories in years. Many New England birders, including several EMHW members, were able to get their binoculars on this unlikely and spectacular visitor.

Steller’s Sea-Eagle is one of the largest and rarest raptors in the world. An 8-foot wingspan is among the longest of all eagles. The imposing orange-yellow bill and brilliant white upperwings make adult birds unmistakable and striking. A resident of Northeast Asia, they are listed as a vulnerable species and populations are estimated globally at just 5,000 individuals, with that number in decline. While occasionally observed across the Bering Strait in coastal Alaska, this species had never previously been reported in Canada or the lower 48 US states. EMHW Director Bob Secatore remembers many years ago coming across a spectacular color plate of the bird in Brown and Amadon’s Eagles, Hawks and Falcons of the World, recalling the caption “this magnificent eagle…would be a candidate for the title of the world’s most impressive bird.”

The story began with a series of one-off sightings far from our area. An August 2020 report of a Steller’s Sea-Eagle in Alaska didn’t make it onto the radar of most birders, but a suspicious photo from Texas in March 2021 did and seemed improbable. Then came a series of sightings in New Brunswick and Quebec between June and August; then Nova Scotia in November. All were eye-opening and indisputable encounters. Photos showed solid evidence that this was the same individual eagle in each case. Where would it show up next?

The eagle evaded detection for five weeks, until December 12th, when it was photographed on the Taunton River in Dighton, Massachusetts. It wasn’t until December 19th that word of the eagle’s presence became public knowledge, setting off a frantic search effort the next day. At dawn on the 20th, the eagle was refound–and thus a small patch of river in Eastern Massachusetts instantly became the eye of a massive storm of birding excitement.

Hundreds of birders descended on the scene almost immediately, enjoying inconceivable views of the eagle hunting, flying, and even vocalizing. EMHW Founder and Director Paul Roberts was present on the 20th to see the bird. His first impression? “I was blown away by the size – it was so much bigger than the immature Bald Eagles perched next to it.” At 1pm, six hours after being refound, the Steller’s Sea-Eagle took flight and departed to the north. Roberts remarked, “I was even more impressed when it took off. It was so immense–it was like the Missouri after WWII, the biggest battleship out there, going around slowly in the air.” The eagle would not be seen in Massachusetts again.

The story picks back up in Midcoast Maine on December 30th, when the eagle was spotted again. It made regular appearances through January, delighting thousands of visitors to the area. EMHW Director Will Martens made an overnight trip and picked up the eagle on the second day near Boothbay Harbor. He noted, “It was such a massive bird, the top of the evergreen tree was bending.” Paul Roberts found the eagle’s consistency remarkable: “The fact it almost behaves in a statesman-like way that allows itself to be seen…the Steller’s Sea-Eagle was passing in review in a way that most raptors do not…maybe it knows it’s something special.”

Sightings continued sporadically in Maine through February and March as the initial excitement died down. In April, it was back to Nova Scotia, and as of press time, last spotted in June in Newfoundland.

For Will Martens, it will go down as one of his top raptor sightings ever: “It was a great experience; we met a lot of people and saw some really nice places. The Maine coast was gorgeous, even in the freezing cold…we were happy the whole way home.” Bob Secatore saw the eagle briefly and distantly twice in Maine, but remains hopeful for another chance: “I’m still hoping to get another crack at someday seeing it unobstructed at a reasonable distance even if I have to go to Nova Scotia or Alaska…or even Asia if that’s what it takes.“

(2021) The Kestrel from Across the Pond

By Brian Rusnica, President, EMHW, with Shawn Carey, Paul Roberts, and Bob Secatore

In 2021, the Plum Island Hawk Watch reported an uncommon visitor to the site: a Eurasian Kestrel (Falco tinnunculus). This widespread raptor is common to Europe, Asia and Africa, but extremely rare in the Americas. However, this is not the first time that they’ve been observed in Massachusetts. In fact, it’s not the first time one has made it into an EMHW count. Who is this enigmatic bird, and just how significant was this year’s find?

The Eurasian (also called Common) Kestrel is vaguely similar to our American Kestrel: a rufous-backed falcon with thin, pointed wings and a long tail. They are sexually dimorphic, like our American birds, with males more variably-colored than females. The adult male features a bluish-gray head with a single malar stripe, a bluish-gray tail with black subterminal band, and a rufous back with sparse black spotting. The adult female is a more uniform color: a rusty-brown, with black banding throughout the back and tail, and lacking the male’s gray head.

A key difference that may not be well-known is size! Eurasian Kestrels are longer, twice as heavy, and have proportionally longer tails and wings than American. Indeed, they are even larger than Merlins across the board.

The first state record of Eurasian Kestrel dates back to 1887 in Hull. The second came over a century later! In Spring 2002, a male Eurasian Kestrel was reported in Wellfleet and Chatham and accepted by the Massachusetts Avian Records Committee. Leslie Bostrom first spotted the bird on April 14th in Wellfleet, and it hung around Cape Cod until May. EMHW’s Shawn Carey recalls that the sighting came as Email was starting to revolutionize local birding, drawing crowds of up to 50 people looking for the new celebrity bird. “If you were a Massachusetts birder and you were a lister, you got the triple crown: you got it on your Year List, your Massachusetts list, and your ABA List.” When he finally got the Kestrel in his sights in Chatham, Shawn said the experience was “phenomenal – you couldn’t ask for better looks at it.”

A sighting that was not accepted by the State committee was a brief 2009 observation by EMHW founder Paul Roberts. On April 13th, Paul was at the Plum Island watch when he picked up an unusual raptor coming North. “I focused right on the bird with the scope at eye level and got a chance to watch” before he tried to get the rest of the crew on it. Paul right away saw a bird bigger than an American Kestrel, with one weak malar bar, and a distinctive dark tail band. His previous experience with species led to a confident ID of a female Eurasian Kestrel.

That 2009 flyby was not Paul’s first Plum Island encounter: in April 1995, while on Lot #1 duty with watcher Joe Hogan, he had a close view of a perched bird that he first thought might be an aberrant female American Kestrel. Roberts recalls, “We got really good looks at it…I had never seen a Kestrel with one [malar] mark, and that was the thing that just blew me away…It looked large, but it was the facial pattern was really very distinctive, and it was unidentified, so that’s what it went down as.” At the time, Paul didn’t have any guides that showed a match for this raptor, so it required some consultation-by-mail with raptor author Bill Clark before they eventually resolved an ID of female Eurasian Kestrel.

Later, when Paul told fellow watcher Ed Mair the 1995 story, Ed relayed that an Unidentified Falcon from the Plum Island hawkwatch the year before in 1994, had two-toned upperwings “unlike any American Kestrel he had ever seen.” Ed concluded that bird was also likely a Eurasian Kestrel.

Bob Secatore’s 2021 flyby sighting was also a brief one, but to him it was obvious the raptor was not one of our typical stock. Early on April 13th, Bob was the only observer on duty when he caught an extremely low but close raptor moving through Lot #1. Bob saw the lanky, long wing and tail dimensions of a falcon, but thought “immediately, it was way too big for a Kestrel.” Yet the bird showed a rusty, barred topside, but “the head pattern had nothing to do with our Kestrel at all, nor a Peregrine or Merlin.” The odd combination of size and plumage left Bob noting, “It certainly wasn’t any falcon that we had around here…something very, very different that wasn’t on our typical agenda down there, in terms of species.” From a previous conversation with Paul on the topic of this species, Bob had formulated the Eurasian Kestrel ID quickly and logged it on the day’s count. While this sighting was over in a flash – it was unforgettable. Bob remarks, “it happened instantaneously…but it was definitely one of the highlights of my year.”

While Eurasian Kestrel sightings in Massachusetts are too few and too brief to formulate much deep analysis, the excitement that their visits generate is palpable. There is still much we don’t know – including whether these birds are flying in from across the Atlantic, crossing on ships, or are part of a North American stock that now migrates on our side of the pond. We look forward to their next arrival at one of our hawkwatch sites.